The National Center for Civil and Human Rights brilliantly interweaves the history of the American Civil Rights movement with current global human rights issues. It is a powerful and thought-provoking museum best understood and appreciated by adults and older children.

The museum is located on the same grassy grounds as the Georgia Aquarium and the World of Coca-Cola, across from Centennial Olympic Park. The land was donated by the Coca-Cola Company, giving the museum a prime location adjacent to some of Atlanta’s top tourist attractions. Designed by architect Philip Freelon, it is an impressive building from the outside. The center’s huge glass facade is cupped by two large, curving walls, meant to evoke a feeling of unity created by two hands coming together.

We walked past the building several times over the weekend before we stumbled across the stunning sculpture on the east side of the building. Two 32 foot glass panels housed in curved steel frames rise from the plaza on the lower level of the museum grounds. Quotes from Nelson Mandela and Margaret Mead are etched into the glass, and water flows over the glass and words. It is a beautiful and powerful addition to the museum. While it fits beautifully into its location on the plaza along Ivan Allen Jr. Boulevard, I can’t help but think it is missed by so many visitors because it is tucked away on the backside of the building. But perhaps this was intentional – my son and I were the only two down there and it was a poignant moment standing there in silence reading the quotes.

We used our CitiPASS tickets and walked into the light filled atrium. The glass wall at the front of the building stretched three stories tall and spread light throughout the museum. There are three main permanent exhibits – The American Civil Rights Movement, The Global Human Rights Movement, and The Morehouse College Martin Luther King, Jr. Collection.

The civil rights exhibit is on the ground floor and where we started our museum tour. In contrast to the bright lobby, the first exhibit room was dark, a fitting representation of a dark period in our nation’s history. Here we learned about life in Atlanta during the Jim Crow era. Sweet Auburn is a historic African-American neighborhood in Atlanta and the right hand side of the room was dedicated to the history of the neighborhood and its landmarks.

On the left hand side of the room was an interactive display of Jim Crowe laws. Visitors could select a state and push a button to make the exhibit spin to display Jim Crow laws from that state. I think this part of the exhibit was one of the most impactful for our kids. They knew about Jim Crow laws and that blacks and whites had separate bathrooms, water fountains, etc. But to see the depth of the segregation was really eye opening for them. An example from Georgia that stood out to my baseball-loving son: “It shall be unlawful for any amateur white baseball team to play baseball on any vacant lot or baseball diamond within two blocks of a playground devoted to the Negro race, and it shall be unlawful for any amateur colored baseball team to play baseball in any vacant lot or baseball diamond within two blocks of any playground devoted to the white race.” It was stunning to him that not only could kids from the two races not play against each other, they couldn’t even play within two blocks of each other.

The most dramatic and powerful part of the exhibit is the interactive lunch counter. Here visitors can sit at a lunch counter and put on headphones to experience what it was like at a sit-in in the 1960s. The exhibit challenges you to sit with your hands on the counter and your eyes closed while angry voices hurl insults and slurs at you through the headphones. A clock keeps count of how long you can last. The degree of hate was so unbelievably high it brought tears to my eyes. The volume of the angry voices, shattering glasses, banging tables and clattering silverware, combined with the actual words being yelled were too much for me to take. I couldn’t make it through the 90 seconds. It was sobering to think that African Americans faced this kind of anger and hate day in and day out without the option to just walk away from it like we did.

A sign on the line for the lunch counter exhibit warns of its disturbing content and recommends the experience for ages 14 and up. We allowed our kids to watch others participating and explained to them what was happening. We then gave them the option to try it or not. Our 11 year old tried it and our 9 year did not. RB lasted about 20 seconds and was clearly upset when he walked away but I think he was glad he did it to briefly put himself into the protestors’ shoes and better understand what they endured. I think the 14 guideline is a pretty good one, although mature kids in the 10+ age range will probably be ok with proper warning before hand. I was horrified to see someone put the headphones on their 3 year old, who almost instantly burst into tears and had to be carried out of the room screaming. There was absolutely nothing for a child that age to gain from hearing that and I have no idea what his parents were thinking.

The museum moves from some of the darkest moments in our country’s history to a moment of hope and light with its exhibit on the 1963 March on Washington. You literally emerge from the dark exhibit rooms on segregation into a room of light. There is a beautiful display spanning two walls depicting the timeline and key figures in the march. Above the display is the last paragraph from Martin Luther King Jr’s I have a dream speech: “When we allow freedom to ring – when we let it ring from every city and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, “Free at last, Free at last, Great God a-might, We are free at last.” This room is enlightening and evokes a sense of hope.

But of course we know from history that the civil rights movement was a series of steps forward and then back. The “On That Day” exhibit (again in a dark room) depicts the day that Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered. Actual news footage of Walter Cronkite reporting on the assassination is played, and historical artifacts and recreated details are on display, giving you a feel for that fateful day.

But all hope is not lost. The final, light-filled room celebrates the martyrs, those individuals who “died in ways related to the civil rights movement.” While the people honored here made the ultimate sacrifice, they helped advance the cause and, while we still have a long way to go, we can see how far we have come from the Jim Crow days depicted at the beginning of the museum.

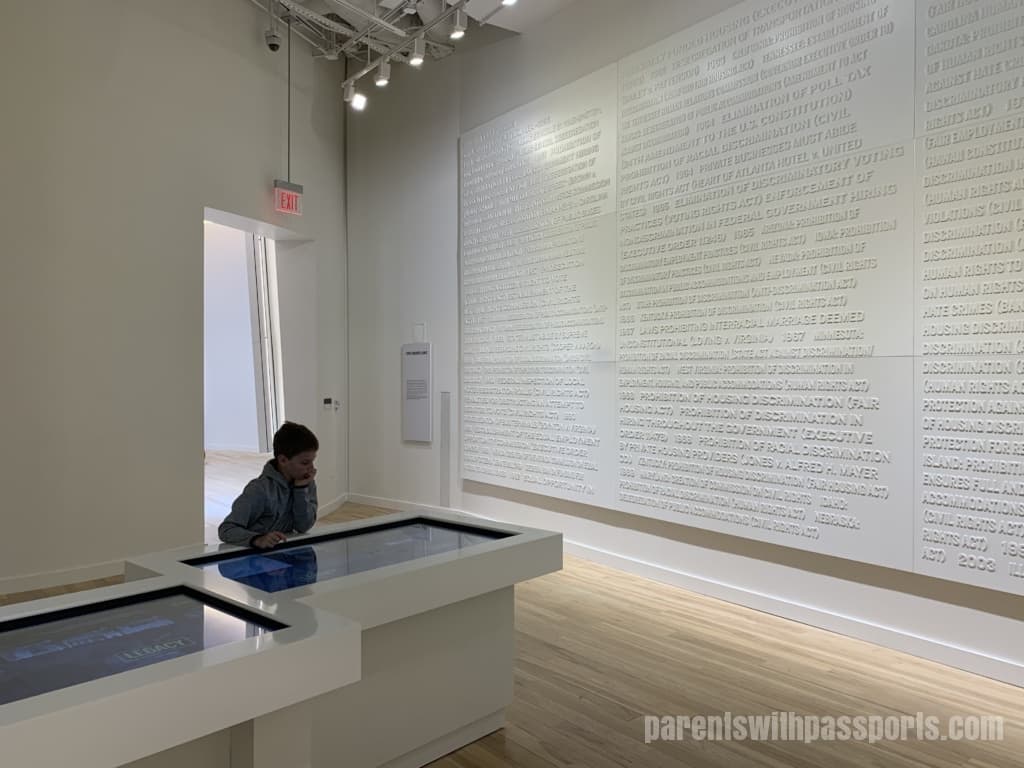

Exiting the martyr room brings you to the upstairs lobby, which has an exhibit on breaking barriers in sports, featuring the likes of Arthur Ashe and Billie Jean King. You then enter the Human Rights exhibit, which celebrates human rights campaigns since the end of World War II. The exhibit features a wall of some of the most famous violators of human rights on one side – Hilter, Stalin, Mao – and some of the most famous defenders on the other – King, Gandhi, Mandela. In the center, it also celebrates the individuals today who continue fighting for human rights in different areas.

There are also two mini-theaters where visitors can sit under a cone and watch videos on human rights. My 9 year old sat and watched a video about detention centers at our borders. He was stunned when I told him that what he saw was happening right now. “What do you mean this is happening now? How can that be?”

The back section of the exhibit gives examples of human rights violations today – children forced to stitch soccer balls in Pakistan, workers in the flower industry inhaling toxic pesticides. And finally, the back wall provides a visual representation of the degree to which the world is free (or not), measuring the level of political rights and civil liberties in each country of the world. Seeing the amount of orange (“partly free”) and red (“not free”) in the world is sobering.

We didn’t make it to the last permanent exhibit – a gallery of Martin Luther King Jr’s papers and artifacts. It is on the lower level and (much like the sculptures outside) can be easily missed if you don’t know it is there.

The museum is really well done. The design, from the exterior architecture to the interior lighting, is all well thought out and meaningful. It is emotional and thought-provoking. We all got a lot out of it. Both kids were moved by the experience. My youngest kept saying it was sad. And it is. But it is important for kids to know this history and to understand both how far we have come and how far we have left to go.

I recommend this museum for mature older elementary / middle school students and up. Younger kids won’t get much out of it because the issues are complex, and the harsh reality of history can be too much for them to handle.